INTRODUCTION

The following is an outline of the 12 questions that are set out in the Education and Learning Issues Paper published by the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People With Disability (Disability Royal Commission).

This outline is not intended to be prescriptive or comprehensive. It is merely designed to identify some common themes for people with disability and families seeking to ensure inclusive education as the human right of students with disabilities, and to assist them in considering developing their own submissions to the Disability Royal Commission and in response to the Education and Learning Issues Paper.

It is important to note that submissions are critical to inform the work of the Disability Royal Commission. It is very important that the Royal Commission understands the importance of ensuring that all children have access to a quality and genuinely inclusive education and the reforms that are needed to ensure this happens across all Australian education systems.

If you are considering making a submission, the information that you provide and the length is entirely up to you – one paragraph by email, or several pages, answers to all 12 questions or just the points you would like to make, your personal story or just your thoughts on why inclusive education matters. We recommend that you use the words “Submission – Education and Learning Issues Paper”. It can be be emailed to DRCenquiries@royalcommission.gov.au or posted to: GPO Box 1422, Brisbane Qld 4001.

Also, you can make multiple submissions, about education or any other relevant matter. This means that you can follow up with more information later.

However, before preparing and submitting a submission, you should read this Disability Royal Commission Education and Learning FAQ Sheet from the Australian Coalition for Inclusive Education and also the information from the Disability Royal Commission on “Confidentiality and protections for people engaging with the Royal Commission” and “Support services during the Royal Commission”.

If you have any feedback on this document please Contact Us.

VIOLENCE, ABUSE, NEGLECT AND EXPLOITATION

Q1 – Are particular forms of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation more prevalent in education and learning environments?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include experiences in relation to:

- The practice of segregating students with disabilities. This is the denial of the right to education on an equal basis and a form of educational neglect.

- The use of restraint and seclusion against students with disabilities.

- Failures to provide academic supports to students with disabilities.

- Failures to provide academic supports to students with disabilities.

- The impact of microaggressions, ableism and educational shortfalls.

- The impact of school bullying. Schools should be able to protect children with disability against bullying while maintaining their inclusion into general education settings.

Q2 – Does the extent or nature of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation of people with disability vary between: a. stages of education and learning (i.e. early childhood, primary, secondary, tertiary, further education)? b. settings of education and learning (i.e. inclusive, integrated or segregated)? c. States or Territories? d. government, Catholic or Independent education systems?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include experiences in relation to:

- Ableism. This is at the core of all violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation is disability prejudice (ableism), so it generally affects all contexts for people with disabilities.

- The impact of segregation. Note that research indicates that disability segregated models for delivery of education to students with disabilities are less safe in that it is easier to conceal violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation so it is more likely to go undetected, be more serious and be carried out for longer. Please share any information you have about this.

- The impact of inclusion and how genuinely inclusive environments can help to keep children with disabilities safer.

Q3 – Taking an intersectional approach, how do the specific experiences of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation vary amongst students in education and learning environments?

Around the world there are some well-established links between segregation and ethnicity or race and in Australia there is increasing research that suggests that First Nations students and children in out of home care are particularly affected by segregation and exclusion policies.

There is also some evidence of a correlation between segregated settings being more clustered in lower income areas.

Please share with the Disability Royal Commission any information about your personal experience of these matters including in relation to segregation, suspensions and expulsion.

Q4 – What are some of the underlying causes of the issues and barriers (outlined in Section 2)? How do these issues and barriers link to or influence the experiences of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation by people with disability in education and learning environments?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include your experiences around:

- Difference and disability being viewed negatively. For example:

- focus on diagnosis not individual needs of the child;

- stereotyping;

- social rejection; and

- devaluation.

- The impact of negative attitudes and beliefs about disability and education. For example:

- failure to recognise equal rights to education – “gatekeeping”, saying “we don’t have funding”, “we don’t have the skill”, suggesting the learning of non disabled students will be prejudiced, excluding students with disabilities from some activities including excursions, concerts, etc;

- low expectations for students with disabilities;

- deficit “medical model” thinking that focuses on “fixing” children with therapies, not providing supports and accommodations;

- entrenched values in the education system that privilege students who are high attaining academically and disadvantages those who aren’t including many students with disabilities;

- the “othering” idea that students with disabilities are one homogeneous group and are distinct from the rest of society – and should be segregated or congregated for that reason.

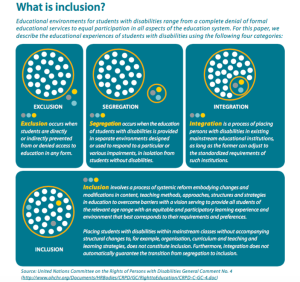

- Poor practices and “integration” instead of genuine inclusion. Note that “integration” is when students are physically placed in regular classrooms but do not get adequate supports and accommodations. This is NOT genuine inclusion.

- Insufficient or unhelpful professional development for principals and teachers.

- Lack of resources. For example, when students denied AAC, etc.

Q5 – What measures and mechanisms prevent violence, abuse, exploitation and neglect of students with disability in education and learning environments? What role does or could inclusive education play in preventing violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation in society?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include:

- The importance of challenging “dangerous assumptions” about disability and education, noting that education is a human service and all human services are based on assumptions. Common “assumptions” include that people with disabilities:

- should be segregated;

- should be grouped with ‘their own kind’;

- cannot be engaged in the regular class work; and

- even when there is some inclusion (with pull-outs for special classes) or placement in a mainstream classroom with an aide, these assumptions still drive the approach.

- The academic and social outcome of ALL students improve when “assumptions” change to:

- all students share similarities and differences;

- students learn best together;

- all students can be engaged in the same lesson material if adapted and appropriate supports provided.

- The need for schools to adopt trauma-informed and rights-based approaches that respect diversity and the rights of the child.

- The need for schools to develop positive and inclusive school cultures, and accessibility, responding to students’ academic and social and emotional needs. Noting that segregation has been found to be a “setting based” risk factor that heightens risk of abuse of children with disabilities (see Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Final Report in 2017).

- The importance of robust and enforceable legal and policy frameworks that comply with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilties and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (eg the Disability Discrimination Act and the Disability Standards for Education are not enough).

- Data collection and monitoring, including on school attainment and outcomes.

Q6 – What barriers or impediments are there to identifying, disclosing and reporting gviolence, abuse, neglect or exploitation in education and learning settings?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include:

- That parents may not be in a position to identify educational neglect of a child with a disability due to lack of information, low expectations, reliance on third party advice.

- The power imbalance between parents and the education system. Parents are often too fearful or intimidated and may fear retribution against their child, to escalate or make a formal complaint.

- The fact that parents are sometimes “burnt out” or traumatised dealing with other issues or accessing disability supports (e.g. NDIS)

- The fact that some children with disabilities who experience violence, abuse or neglect are not able to communicate this effectively.Inclusion can be protective because other children or siblings are more likely to witness and report incidents.

- The lack of strong enforceable rights (Disability Discrimination Act and Disability Standards for Education).

- The fact that complaint mechanisms are generally ineffective and inadequate. Some families have experience of ‘blow back’ or retribution for raising issues and official complaints.

- The devaluation of students with disabilities and negative attitudes cultures that may play a part in creating a culture of school staff not reporting violence, neglect and abuse.

REPORTING, INVESTIGATING AND RESPONDING TO VIOLENCE, ABUSE, NEGLECT AND EXPLOITATION

Q7 – What barriers or impediments are there to adequately investigating violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation in education and learning settings?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include:

- Devaluation of students with disabilities and a negative attitudes culture playing a part in creating a culture of school staff not investigating violence, neglect and abuse.

- Lack of procedures and knowledge on how to capture student voice and experience.

- Difficulty for parents in obtaining information – may only see bruises, scratches or notice changes in behaviour.

- Segregation – in closed environments for people with disabilities, other “witnesses” may be less able to community violence, abuse or neglect.

- Power imbalance between parents and the education system – resources, access to legal services, etc. Pressure put on families to prove claims and disability of child often used against child in calling out “behaviours”.

- Lack of independence and accountability across multiple levels – regional, school and specialist roles.

- Lack of follow up on suspensions and exclusions and underlying causes or triggers i.e. what happened, what was missed, what needs weren’t met.

Q8 – Are there good practice examples that encourage reporting, effective investigation and responses to violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation in education and learning settings?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include:

- The power of inclusive school culture based on respect for rights and human dignity. This encourages broad responsibility for the experiences and well being of every member of the school community.

- Accountability through data collection and monitoring as well as effective complaints mechanisms. Moving beyond the collection of data on attendance, discipline, disability and adjustments to include access, attainment and satisfaction.

- Recognising, supporting, and utilising “children’s voice”.

EDUCATION AND INCLUSIVE SOCIETIES

Q9 – What has prevented Australia from complying fully with is obligations in Article 24 of the CRPD? What needs to change within (a) Commonwealth, State and Territory governments, (b) schools and communities, and (c) individual classrooms, to ensure an inclusive education system at all levels?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include:

- The reality that people with disabilities and their families have great difficulty in holding governments accountable.

- Initial and over emphasis on physical presence has resulted in “integration” – business as usual with “add-ons”. Whole of system reform is needed to ensure inclusive education.

- Lack of political will and the impact of “vested interests” (including teacher unions and “special education”). Do you have experiences of dealing with politicians?

- The failure of governments to set up robust legal frameworks in support of inclusive education for students with disabilities, which has resulted in States and Territories continuing to operate education systems that deny students with disabilities the right to education on an equal footing.

- Lack of appropriate regulation of school admissions and school access, lack of enforceable rights, lack of enforceable systemic standards and lack of monitoring (and collection of data) continue to play a significant role.

- In many cases, education policies that have, deliberately or by omission, failed to define “inclusive education”.

- Continuous investment in a dual track system subverts any other efforts made e.g. high schools appear to struggle with meaningful inclusion for many and there appears to be no effort to look at learning as progression for students with disability.

- Deeply rooted prejudice within the education system.

- Continued reliance on the resilience of children and their families to advocate for themselves and build skills regardless of appropriateness. This is unfair.

- Segregation being still seen as a form of “benevolence” – there are deeply entrenched cultural views about how society should respond to disability that run counter to a rights-based approach to education.

- Under the current system, the wide margin of discretion given to school principals and educators when it comes to providing reasonable adjustments.

- Funding and financial arrangements that provide individual and systemic incentives to segregate – both for education systems, schools and parents.

Q10 – What is essential to facilitate the transition from segregated or integrated settings to inclusive education settings, and to sustain the change?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include:

- The critical importance of the recognition of inclusive education as a fundamental human right.

- Effective efforts to create cultural change within schools and beyond: Inclusive education requires a change in perspective, from seeing certain children as a problem to identifying existing needs and improving the education system itself. This requires investment in changing attitudes and promoting a positive school climate where diversity is recognised and accepted.

- Comprehensive review of current laws, policies and education practices to identify current gaps and deficiencies, including funding.

- A National Inclusive Education Plan to drive implementation of an inclusive education system and sustain inclusive education, including a desegregation strategy, clear targets and an ambitious timetable, long-term objectives and sufficient and appropriately allocated resources – as recommended in the CRPD Review Concluding Observations, General Comment No.4 and Federal Senate review into education of students with disabilities – guided by definitions in General Comment No.4 as the applicable standard.

- The need to look to learning from Australian schools that are running good practice inclusive models or have successfully “transitioned” out of segregated models (i.e. closed education support units or special classrooms) and also schools transitioning out of “integration” models to genuine inclusive models. Good knowledge and practices should be shared and encouraged through professional and funding incentives.

- The need to establish robust legal and policy framework to support not only a “non-rejection” default position but also a comprehensive and explicit legal prohibition of discrimination against individual students with disabilities, covering segregation, integration and exclusion and “gatekeeping” practices, but also provide for systemic transformation and implementation of obligations of the CRPD (Art 24) in relation to the education system itself.

- The importance of disaggregated data, effective monitoring and evaluation mechanisms

- Educating and upskilling education stakeholders (training and professional incentives).

- Creating formal pathways for parent-teacher collaboration especially in developing reasonable adjustments and supports for individual students.

- Building department and school capacity for sustainable inclusive education practices – eg. universal design for learning approaches, differentiated instruction, use of teacher aides inclusively, behaviour supports, co-teaching, data based instructional decision-making, peer-supported learning, culturally responsive teaching.

- Appropriate regulation of “school choice” to ensure it is not generating discrimination. Note that parents often decide to send their children to segregated settings because of significant “gatekeeping”(as confirmed by research and number inquiries and reports) and lack of quality evidence-based information. In most cases these choices cannot be said to be free or informed.

Q11 – What is the impact of inclusive education on the life course outcomes (including learning and employment outcomes) of students with disability? And students without disability?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include:

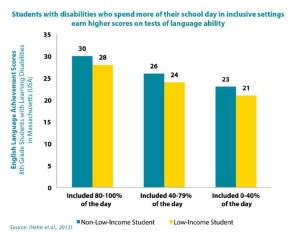

- The harm of segregation to students with disabilities, socially and academically. Note that “There is no research that supports the value of a segregated special education class and school” (A “The Segregation of Students with Disabilities”, National Council on Disability (USA, independent federal agency) (2018)

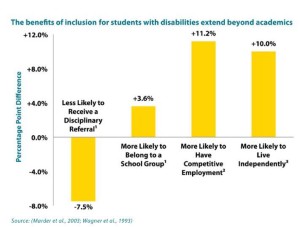

- Segregation reduces the opportunity for students with disabilities of acquiring essential life skills through contract with others. It often sets students up for more segregated models – sheltered workshops, group homes.

- The beneficial impact of inclusive education on non-disabled students: Research has also shown consistently that children who share inclusive classrooms with children with disabilities have more positive attitudes towards difference, better social skills and awareness, less disruptive behaviours and more developed personal values and ethics (Hehir, 2007 comprehensive review).

- The detrimental impact of segregation on siblings.

Q12 – How does inclusive education promote a more inclusive society?

There are many things that families could share with the Disability Royal Commission in response to this question. Some things to consider include:

- The role of schools in defining the values for societies in the future.

- The role of inclusion at school a necessary foundation for the development of inclusive communities. Inclusion of people with disabilities in society cannot happen while they are kept apart, as long as we keep perpetuating “special places for special people”.

- The growth of respect and understanding when students of diverse abilities and backgrounds play, socialize, and learn together. This includes access to socialisation experiences outside the classroom – after- school activities, youth camps, etc. – where students also acquire skills and competencies that are key for future work and life.

- The role of education models that exclude and segregate students on the basis of disability in perpetuating discrimination against people with disability, denying them social and academic opportunities on an equal footing with others, reinforcing prejudices against them and weakening the bonds of social cohesion.