Introduction

For over 40 years, the body of relevant research into education of students with disability has overwhelmingly established inclusive education as producing superior social and academic outcomes for all students. Further, the research has consistently found that academic and social outcomes for children in fully inclusive settings are without exception better than in the segregated or partially segregated environments (e.g. “education support units” or “resource classrooms”). Unfortunately segregated education remains a practice that has continued mostly for historical reasons and which continues to be suggested to families and educators as an appropriate option, despite having virtually no evidence basis.

The most recent comprehensive review of the research was undertaken by the Alana Institute and presented in an international report entitled “A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education“ released in 2017. The Report was prepared by Dr Thomas Hehir, Professor of Practice in Learning Differences at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in partnership with global firm Abt Associates.

The Report is essential reading for education administrators, teachers and parents in documenting the results of a systematic review of 280 studies from 25 countries.

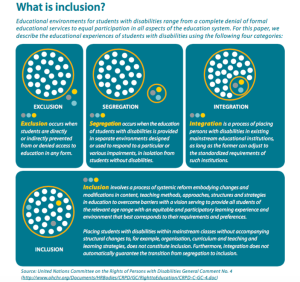

The Report defines inclusive educational settings in accordance with General Comment No. 4 (The Right to Inclusive Education), recently released by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. In particular, the General Comment defines non-inclusion or “segregation” as the education of students with disabilities in separate environments in isolation from students with disabilities (i.e. in separate special schools or in special education units co-located with regular schools). [p3]

The Report recognises that the growth in inclusive educational practices stems from increased recognition that students with disabilities thrive when they are, to the greatest extent possible, provided with the same educational and social opportunities as non-disabled students [p4]

The Report also acknowledges the significant barriers of negative cultural attitudes and misconceptions amongst school administrators, teachers, parents (including some parents of children with disabilities) and communities to the implementation of effective inclusive education and notes the need for general societal education as to the benefits of inclusive education.

Key findings of the Report

1. There is “clear and consistent evidence that inclusive educational settings can confer substantial short and long-term benefits for students with and without disabilities”. [p1]

- “A large body of research indicates that included students with disabilities develop stronger skills in reading and mathematics, have higher rates of attendance, are less likely to have behavioural problems, and are more likely to complete secondary school than students who have not been included. As adults, students with disabilities who have been included are more likely to be enrolled in post-secondary education, and to be employed or living independently.” [p1]

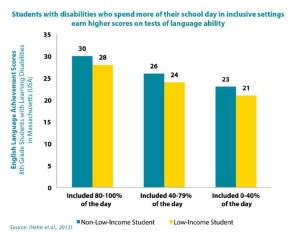

- Multiple reviews indicate that students with disabilities educated in general education classrooms outperform their peers who have been educated in segregated settings. A 2012 study by Dr Hehir examined the performance of 68,000 students with disabilities in Massachusetts and found that on average the greater the proportion of the school day spent with non-disabled students, the higher the mathematic and language outcomes for students with disabilities. [p13]

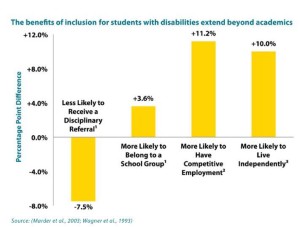

- The benefits of inclusion for students with disabilities extend beyond academic results to social connection benefits, increased post-secondary education placement and improved employment and independence outcomes. [p15] There is also evidence that participating in inclusive settings can yield social and emotional benefits for students with disabilities including forming and maintaining positive peer relationships, which have important implications for a child’s learning and psychological development. [p18] Again, there is a positive correlation between social and emotional benefits and proportion of the school day spent in general education classrooms. [p19]

- The Report states that “…research has demonstrated that, for the most part, including students with disabilities in regular education classes does not harm non-disabled students and may even confer some academic and social benefits. … Several recent reviews have found that, in most cases, the impacts on non-disabled students of being educated in an inclusive classroom are either neutral or positive.” [p7] Small negative effects on outcomes for non-disabled students may arise where a school ‘concentrates’ students with severe emotional and behavioural disabilities in the one class (itself a form of segregation) rather than distributing those students across classrooms in their natural proportions. [p9]

- “A literature review describes five benefits of inclusion for non-disabled students: reduced fear of human difference, accompanied by increased comfort and awareness (less fear of people who look or behave differently); growth in social cognition (increased tolerance of others, more effective communication with all peers); improvements in self-concept (increased self-esteem, perceived status, and sense of belonging); development of personal moral and ethical principles (less prejudice, higher responsiveness to the needs of others); and warm and caring friendships.” [p12]

- An extensive recent meta-analysis covering a total sample of almost 4,800,000 students has also confirmed the finding that inclusive learning environments have also been shown to to have no detrimental impact, and some positive impact, on the academic performance of non-disabled students.

2. Teaching practice is central to ensuring that inclusive classrooms provide benefits to all students. [p9]

- Teachers with positive attitudes towards inclusion are more likely to adapt the way they work for the benefit of all students and are more likely to influence their colleagues in positive ways to support inclusion. [p9]

- Research suggests a positive correlation between teacher training and positive attitudes towards inclusion. [p9]

- Though financial resources matter, implementing inclusive education requires teachers and other educational professionals to regularly engage in collaborative problem solving. Research suggests that it is through the development of a culture of collaborative problem solving that the inclusion of students with disabilities can serve as a catalyst for school-wide improvement and yield benefits for non-disabled students. [p10]

Key Report Recommendations for Fostering Inclusive Education [pp.22-25]

- [Establish an expectation for inclusion in public policy] National policy, publicly endorsed by national leaders, must affirm the right of students with disabilities to be included along-side their non-disabled peers.

- [Establish a public campaign to promote inclusive education] Changing public opinion about the importance of inclusive education, especially for students with intellectual disability, is important. Long-standing misconceptions about the capacities of students with disabilities to thrive in an inclusive classroom must be countered – teachers, school administrators and parents must be supported and educated so that students with disabilities experience effective welcoming schools and classrooms that meet their needs.

- [Build systems of data collection] Countries must invest in collecting accurate data on the degree to which students with disabilities have access to general education, including the amount of time actually spent in general education classrooms. This data can be used to identify schools and communities in need of support in better educating and including their students with disabilities.

- [Provide educators with a robust program of pre-service and in-service preparation on inclusive education] First, attitudes matter a great deal and attitudes among educators are often negative, and those attitudes can carry over into the classroom and the school. Teachers and school leaders need opportunities to both confront these attitudes and to see how successful inclusion can work. Secondly, educators must learn classroom techniques that can help students with disabilities to thrive – in particular, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework – which requires that schools design curricula to accommodate the diverse strengths and weaknesses of all learners – should be used to support teacher development.

- [Create model universally designed inclusive schools] Schools that have done inclusion particularly well should serve as demonstration models for the training of inclusive teachers and school administrators.

- [Promote inclusive opportunities in both post-secondary education settings and the employment market] Post-secondary education and employment settings should be encouraged to expand opportunities for people with disabilities.

- [Provide support and training to parents seeking inclusive education for their children] Parents often need support in seeking inclusive education for their children and in maximising their child’s development. In the United States, parent-training centres have been funded by the federal government to teach parents about inclusive education and to provide them with support in seeking effective inclusive placements for their children.

You can read the full Report here.

Want to know more?

Research on social and academic outcomes:

Reviews and meta-analyses

“Towards inclusive education: A necessary process of transformation” Dr K. Cologon, (2019) for Children and Young People With Disability Australia. [A review of over 200 studies, specifically aimed at providing information to parents.]

“Does Inclusion Work?”, Dr K. de Bruin (2019), Chapter 3 in L.J. Graham (Ed). Inclusive Education in the 21st Century: Theory, Policy and Practice. Sydney: Allen and Unwin [This review of research specifically considers the benefits of inclusive education for students with multiple and complex disabilities.]

“The Segregation of Students with Disabilities”, National Council on Disability (USA, independent federal agency) (2018). [This paper concludes that there is no evidence in support of segregating students with disability from the perspective of social and academic outcomes.]

“Evidence of the Link Between Inclusive Education and Social Inclusion”, European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018). [This review of research of over 250 studies internationally finds a link between school inclusion and post school outcomes such as open employment.]

“A Summary of the Research Evidence on Inclusive Education’”, Todd Grindal, Thomas Hehir, Brian Freeman, Renee Lamoreau, Yolanda Borquaye, Samantha Burke (2016). [A comprehensive review of research led by Harvard, finding that students who are included achieve better social and academic outcomes and there are benefits for non disabled students as well.]

“Inclusive Education of Students With General Learning Difficulties: A Meta-Analysis”, Krämer S, Möller J, Zimmermann F. In Review of Educational Research. (2021) ;91(3):432-478. doi:10.3102/0034654321998072 [A meta analysis representing over 4 mission students concluding that inclusive classrooms with students with disability do not adversely impact on the learning of non disabled students and may even provide benefits for them.]

“A meta-analysis of the effects of placement on academic and social skill outcome measures of students with disabilities” Oh-Young, Conrad & Filler, John. (2015) in Research in Developmental Disabilities. 47. 80-92. 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.08.014. [A meta analysis supportive inclusive education for students with disability from the perspective of social and academic outcomes.]

“Mainstreaming Programs: Design Features and Effects“, Wang MC, Baker ET (1985) The Journal of Special Education. 1985;19(4):503-521. doi:10.1177/002246698501900412

“The Efficacy of Special Versus Regular Class Placement for Exceptional Children: a Meta-Analysis”, Carlberg C, Kavale K. (1980) in The Journal of Special Education. 14(3):295-309

“Research Support for Inclusive Education and SWIFT”, Schoolwide Integrated Framework for Transformation (SWIFT Schools), (January 2017)

“Inclusion or Segregation for children with an Intellectual Impairment: What does the evidence say?” (2008)Dr Robert Jackson, Associate Professor at Edith Cowan University

Recent studies

“Outcomes of Inclusive Versus Separate Placements: A Matched Pairs Comparison Study” (2020), Kathlee Gee, Mara Gonzalez and Carrie Cooper, Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, August 2020

“The Relationship of Special Education Placement and Student Academic Outcomes” (2020), Sandi M. Cole, Hardy R. Murphy, Michael B. Frisby, Teresa A. Grossi and Hannah R. Bolte, The Journal of Special Education, June 2020

Research on segregation:

“The impact of inclusive education reforms on students with disability: an international comparison” (2019), Kate de Bruin, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23:7-8, 811-826. [A study concluding that Autistic students in Australia are being increasingly segregated.]

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse “A brief guide to the Final Report: Disability” (2017). [This report identifies segregation as a setting-based risk of sexual abuse of children with disability.]

“Fighting school segregation in Europe through inclusive education Fighting school segregation in Europe through inclusive education: a position paper Council of Europe” (2017), Council of Europe. [A position paper following a review of education systems across Europe and calling for a de-segregation strategy.]

“Disability and child sexual abuse in institutional contexts, Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse” (2016), Wayland, Sarah & Llewellyn, Gwynnyth & Hindmarsh, Gabrielle. [Research commissioned by the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse identifies segregation as a setting-based risk of sexual abuse of children with disability.]

Research on “gatekeeping”:

“Gatekeeping and restrictive practices with students with disability: results of an Australian survey”, delivered at the Inclusive Education Summit, Adelaide (2017), Shiralee Poed, Kathy Cologon and Robert Jackson. [Research identifying widespread gatekeeping and restrictive practices across Australian education systems.]

“Improving Educational Outcomes for Children with Disability in Victoria” (June 2018), Eleanor Jenkin, Claire Spivakovsky, Sarah Joseph and Marius Smith. [Research identifying widespread gatekeeping and restrictive practices in Victorian education.]

[Cover photo © Ben White; other photos © Alana Institute]

Thank you for visiting our website. You can also keep up with our mission for #edinclusion by liking our Facebook page or following us on Twitter @allmeansallaus