Image description: Photograph of Dr Innes sitting on a swivel chair next to a boardroom table. Dr Innes is a light skinned man with white short hair. He is wearing a back suit, white collared shirt and light tie. He is facing the camera and smiling. To his right is a seated black guide dog. Dr Innes has his arm outstretched touching the dog.

The following speech was delivered by Dr Graeme Innes AM, to the Victorian Academy for Teaching and Leadership’s 2022 Principal’s Conference on 31 May 2022.

Dr Innes is a lawyer, mediator, company director, and human rights advocate and served as Australia’s Disability Discrimination Commissioner from December 2005 to July 2014.

Among his many important contributions to the rights of people with disability in Australia, Dr Innes was also involved in the drafting of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities which was ratified by Australia in 2008 and recognises the right of people with disability to an inclusive education.

Dr Innes is the founder of the Attitude Foundation and sits on a number of boards in the disability sector. He is a frequent commentator about disability issues in the media, with regular appearances on television radio and print media, including on ABC’s The Drum and Q&A.

Dr Innes has generously shared with All Means All his recent speech to Victorian Principles and given his permission to publish it here.

Transformative Possibilities of Inclusion

I acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands on which we meet today.

Tyler was doing well at school. It was term 1 year 2, and he was up and into his uniform every morning. He’d finish breakfast at a rate of knots, kiss the family goodbye, and be out at the bus stop just outside his front door. It was the first pickup of the run, so he jumped in and sat behind the driver. His mum wished his three siblings had been this keen.

Then the calls from the principal started. She said Tyler was well behaved throughout school, and during recess and lunch-time. But at the end of the day, when the kids were lining up for their buses, he was regularly involved in scuffles and fights.

The school had a no tolerance to violence policy, and the principal was concerned. She didn’t want to suspend Tyler for misbehaviour, but she was running out of alternatives.

Mum chatted with other parents of kids with autism with no positive results. Finally, in a last attempt to avoid suspension, she asked the principal if Tyler’s support worker could observe Tyler’s day at school, to see if she could spot the problem. It would be a day from his NDIS plan funds, but she thought it was worth a try.

Jess, his support worker, watched him travel to school, and have a really good day in class. At the end of the day, when classes finished, the kids streamed out into the playground and bus lines. Tyler was not first in line and did not get the front seat. That’s when the fights started.

The fix was simple. Tyler was let out two minutes early each day, and his seat on the bus became his regular seat in an inclusive school community.

Thanks for the chance to speak with you all today. I know the key role you each play in the success of the inclusion of kids with disabilities, and I also know the key inclusion plays in the success of the lives of kids who are included. I say this having experienced inclusive and segregated settings as a student, and having observed and participated in the disability sector most of my adult life. I want to share some of that experience and knowledge with you today.

I didn’t tell Tyler’s story at the beginning of this presentation to suggest that inclusion is always such an easy fix. Inclusion can sometimes be complex, inclusion can sometimes require extra support, extra staff training and extra resources, and inclusion can sometimes be contested – with advocates proposing changes that schools think are difficult or not achievable. But there are two fundamental reasons for including kids with disabilities.

First, it leads to better learning outcomes for all students and safer learning environments for kids with disabilities. I’ll come back to the research on that.

And second, if we are going to build a Victorian and Australian society that includes people with disabilities, we have to start in school environments. That’s where members of Australian society, with and without disabilities, learn how society works. It is completely counterintuitive to segregate children in schools, and then think that we can successfully transition them into an inclusive society. Segregation in schools puts kids with disabilities on what has been very well described as the polished pathway toward segregation in life – where we live, where we work, and how we interact with society.

I went to a segregated school up to year 10. It was a good learning environment for me, I was safe, and I learned successfully. Most of the teachers were excellent and passionate about their jobs. On the downside though, from the time I was four to the time I was sixteen, I had to travel an hour a day to school and an hour back. That was pretty wearing. But most importantly, I had no friends in my local community. My weekends were often lonely, and I did not have that cohort of friends around me for the rest of my life. I don’t suggest that the peer support from other people who are blind or vision-impaired was not valuable. I do suggest that I missed all of those links which we develop throughout childhood, and which often remain with us for many years. That’s my penalty for segregation. Others with disabilities are more harshly penalised.

So let’s look at what the law says about inclusion. There is clear international support through the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities, a UN treaty to which Australia committed more than a decade ago. This treaty requires countries to include students with disabilities.

This treaty is supported by discrimination legislation at both State and Commonwealth levels. This legislation makes it unlawful to discriminate against students with disabilities by, among other things, excluding them from schools and educational environments. This legislation was passed by State and Commonwealth governments at different times, but has been in place for thirty years or more in most cases. The Commonwealth legislation is supported by Standards under the Disability Discrimination Act, which reflect and expand on the content of the law. They were passed more than a decade ago. They, and the State and Federal law, provide that it is unlawful to discriminate against students with disabilities in a range of ways, including exclusion from education settings. They go further and require education providers to make reasonable adjustments to facilitate the inclusion of students with disabilities. The only exception to this is where such adjustments would cause unjustifiable hardship to the education provider. So it is expected that education providers will, as part of this process, experience some hardship. It is only when that hardship becomes unjustifiable that the education provider has the opportunity not to provide the adjustment. Finally, these standards require that such adjustments must be made in consultation with the student, or the parents of the student. And this requirement makes absolute sense. Because we, as people with disabilities, and the families of people with disabilities, are the experts on our own lives and our own lived experience. So it would be foolish to make such adjustments without considering that advice.

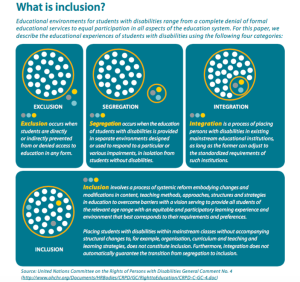

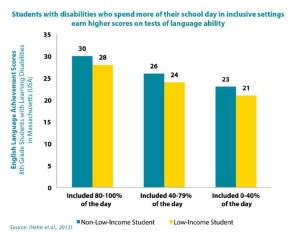

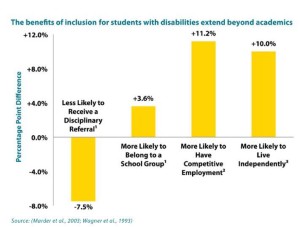

Let me come back, as I promised, to the research supporting the inclusion of students with disabilities. for more than forty years, research into the education of students with disabilities has overwhelmingly established inclusive education as producing superior social and academic outcomes for all students, with or without disabilities. Further, the research has consistently found that academic and social outcomes for children in fully inclusive settings are without exception better than in the segregated, or parties segregated environments, eg education support units or resource classrooms. Sadly, despite this, segregation continues to be suggested to families and educators as an appropriate option, despite having virtually no evidence basis. the most recent comprehensive review of this research was undertaken by the Alana Institute in 2017 at Harvard graduate school of education. Findings set out clear and consistent evidence that inclusive educational settings can confer substantial short and long-term benefits for students with and without disabilities. Included students with disabilities develop stronger skills in reading and mathematics, have high rates of attendance, are less likely to have behavioural problems and are more likely to complete secondary school. They are more likely to be enrolled in post-secondary education and to be employed and living independently. Finally, the benefits received by non-disabled students are equal to, or more positive than, non-inclusion.

None of this is surprising when you think about it. We learn skills, social and academic, as children which we take through the rest of our lives. Why wouldn’t this apply to students with disabilities or non-disabled students who have been educated with students with disabilities?

What I’ve done this morning is focussed on the why for inclusion because I know, if done successfully, the transformative possibilities it can have. I have not focussed on the how. That is for others with more day-to-day education experience than me. But I do know it requires resources, training, and collaborative partnerships to achieve. And I do know that you, as leaders of school communities, can – with the right mindset – achieve those transformative possibilities.

I’ve supported this focus through my own experience, the law, and current research.

But we all know that whilst there are many examples of successful inclusion, inclusion is not happening universally. Why is that, and how can we change that?

I assess that reflecting the whole community approach across Australia, people in the education community have a limiting and negative view of disability. People with disabilities are limited by the soft bigotry of low expectations. Most people in the community make assumptions about us that are negative and wrong. And if the bar is set low for us, most people with disabilities will tend not to push through that bar. We want to be included, we will benefit from being included – and the rest of society will as well. But we cannot be included unless society removes these assumptions, and works with us to make inclusion happen. Education is a microcosm of this situation.

So what can you, as educational leaders, do to change this situation. Well, it’s what many of you are already doing. Rather than saying why it’s saying why not. Rather than making those negative assumptions, it’s setting the assumptions aside. Rather than presuming you know, it’s asking the student or their parents how inclusion might work, and embarking on the journey to make that happen. And taking your school community with you on that journey. Some will come with you happily, some will be reluctant, and others will be unsure. You can use your leadership and skills to set the tone and the direction of the journey.

And what are the results if you take that approach? There are all of the benefits that the research I have referred to lays out for students with disabilities. Plus all of the benefits which the research lays out for the student body as a whole. People with disabilities, such as me, will grow up with their peers, rather than being introduced to them at the end of school when much of our learning and socialising has already occurred. The result will be better social and educational outcomes for everyone and a stronger and more cohesive Victorian and Australian society. And all it takes is making adjustments so that Tyler, and many others like him, get the front seat on the bus.

Thanks for the chance to speak with you today.